An A-Z of modern office jargon

From: http://www.theguardian.com/money/2013/oct/22/a-z-modern-office-jargon

Drill down into this guide and you could be talking like a boardroom legend by end of play. Massive yield!

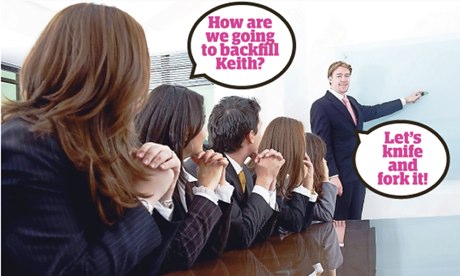

Have you got any idea what on earth they're on about? Photograph: Alamy/Guardian montage

Annual leave

When even the word holiday is thought to sound too frivolous and hedonistic, so that people on their holidays set their out-of-office autoreply to announce grandly that they are instead on annual leave, then surely we have entered a hellishly self-parodic downward spiral of capitalist civilisation.Backfill

After someone has been sacked – sorry, "transitioned" – they tend to leave a person-shaped hole in the landscape. What do you do with a hole, especially a person-shaped one that reminds you a bit of a hastily dug grave? You fill it in – in other words, you backfill (verb), or address the backfill (noun).Originally, backfill was an engineering term, meaning to fill a hole or trench with excavated earth, gravel, sand or other material. Now it means "replacement" or "replace", eg: "We are recruiting for Tom's backfill" or "We will have to backfill Richard." Meanwhile, a job vacancy that exists to replace an ex-employee, as opposed to a newly created role, is called a backfill position, even if that sounds more like something an adventurous type might adopt at an S&M club.

Close of play

The curious strain of kiddy-talk in bureaucratese perhaps stems from a hope that infantilised workers are more docile. A manager who tells you to do something by end of play or by close of play – in other words, today – is trying to hypnotise you into thinking you are having fun. This is not a sodding game of cricket. Though, actually, it appears that the phrase originates from the genteel confines of the British civil service, when there might well have been cricket, or at least a very long lunch, on the day's agenda.Synonymous with asking for something by close of play is requesting it by the end of the day. End of whose day, exactly? Perhaps the boss is swanning off at 3pm while everyone else will have to stay till 8pm in order to get it done. A day can be an awfully long time in office politics.

Drill down

Far be it from me to suggest that managers prefer metaphors that evoke huge pieces of phallic machinery, but why else say drill down if you just mean "look at in detail"? Like many examples of bureaucratese, drill down has a specific sense in information technology: to follow the hierarchical ladder of a data-analysis menu down through to the individual datum. In accounting software, not only can you drill down, drill up and drill in, but you can even drill around, much as a disturbingly incompetent dentist might, or as old-school Texas oil speculators used to do.Expectations

Expectations are flexible things, and people will no doubt carry on having them even if the lingo surrounding them is logically complete nonsense. For example, one source reports: "In a team meeting a few months ago, the then-manager said: 'There's no reason that all of you shouldn't get a rating of Exceeds Expectations every review if you all work hard.' She didn't like it when I pointed out that if she expected us to exceed expectations, it was then literally impossible for us to do so." Touché!It would be good if employees were able to manage the expectations of their managers, but managing expectations usually means something more outward-facing and defeatist: preparing your clients or customers psychologically for the inevitable fact that the "deliverables" will be rubbish.

Flagpole, run this up the

Let's run this up the flagpole! Using this exhortation to mean "give it a try" or "test it" came to prominence in the 1950s Madison Avenue advertising industry. It derived from a yarn that was doing the rounds about the first US president, George Washington. When Betsy Ross presented the new American flag to him, he was supposed to have quipped: "Let's run it up the flagpole and see if anyone salutes it."The original sense was to test something (eg an ad campaign) in public, or at least in front of the clients, rather than just around the office: a nuance that has since been lost.

Later variations on the theme include: "Let's cross the sidewalk and see what the view looks like from over there", or "Let's put it on the radiator and see if it melts", or even (so I am assured) "Let's knife-and-fork it and see what comes out". (Comes out from where? That's disgusting.) There seems no end to the forced jollity (and despair-inducing implied exclamation mark) of such constructions.

Going forward

Top of many people's hate-list is this now-ubiquitous way of saying "from now on" or "in future". It has the added sly rhetorical aim of wiping clean the slate of the past; indeed, it is a kind of incantation or threat aimed at shutting down conversation about whatever bad thing has happened. This aspect of the phrase proves to be especially attractive to politicians, who like to accuse their critics of being mired in the past. The official pronouncements of Barack Obama's administration are littered with going forward, or its sibling moving forward, which at the time of writing have been deployed nearly 600 times in the past year in official White House transcripts and press releases.

Photograph: Getty Images/Vetta/Guardian montage

Photograph: Getty Images/Vetta/Guardian montage Heads-up

"I just wanted to give you a heads-up on …" is now the correctly breath-wasting way to say "I just wanted to tell you about …". Its origin, in American engineering and military circles of the early 20th century, is an exhortation for all the members of your squad or crew to pay attention because something potentially dangerous is about to happen. They should literally straighten their necks and raise their heads. So the call "Heads up!" means "Watch out!"The 1970s saw the invention of the military technology called a heads-up display: crucial information from a fighter jet's instruments was projected on to the cockpit windshield. So heads-up originated in situations where something hairy was about to happen, or where life-or-death information was being provided to an elite warrior. Naturally, neither of those things is ever true when the noun phrase "a heads-up" is used in the modern office. Time, perhaps, for a heads-down, when everyone takes a quiet snooze at their desks.

Issues

To call something a "problem" is utterly verboten in the office: it's bound to a) scare the horses and b), even worse, focus responsibility on the bosses. So let us instead deploy the compassionate counselling-speak of "issues". The critic (and manager) Robert Potts translates "There are some issues around X" as: "There is a problem so big that we are scared to even talk about it directly."What if something is more serious than an issue – an incipient catastrophe that might bring down the whole business? You still can't call it a "problem". But you can express the very deep way in which you personally care about it by referring to it as a concern.

Journey

There's something peculiarly horrible about the modern bureaucratic habit of turning everything into a journey, with its ersatz thrill of adventurous tourism and its therapeutic implications of personal growth. Sometimes the made-up journey is a group affair, like a school outing. So businesses infantilise their employees by saying they have all been on a fascinating voyage together, when in fact many of their colleagues have been brutally thrown from the bus. As one infuriated correspondent explains: "The 'journey we have been on' really refers to 'the ongoing cuts and redundancies in the organisation that I work for.'"Software and web designers will often talk about the user journey, which at least correlates with the metaphor of webpage and interface "navigation". But the British government also explains the process of claiming disability benefit under the rubric "The Claimant Journey", which might be thought rather insensitive to those claimants actually unable to travel.

Key

With your key core competencies, you can no doubt achieve the key performance indicators, take on key challenges, and overcome key issues to meet key milestones and placate our key stakeholders, going forward. But why the hell is everything key? Is there some kind of subliminal phallic titillation to the image of key things penetrating the welcoming oiled openings of locks? You can even have key asks, which are not small free-standing shops that sell newspapers or develop film. I'm tempted to start up a locksmithing business that supplies key keys.Once you start calling so many things key, of course, semantic inflation dissolves its sense almost entirely.

Leverage

The critic Robert Potts reports this parodic-sounding but deathly real example: "We need to leverage our synergies." Other things you can leverage, according to recent straightfaced news and business reports, are expertise, cloud infrastructure, "the federal data", training and "Hong Kong's advantages". To leverage, in such examples, usually means nothing more than "to use" or "exploit". Thus, "leverage support" means "ask Bob in IT"; and I suggest "leverage the drinkables infrastructure" as a stylish new way to say "make the coffee".The appropriation of this financial metaphor doesn't quite seem to have been thought through. The verb "leverage" began to be used in the late 1960s specifically for a technique of speculating with borrowed money. So executives who dream of leveraging synergies seem to be unconsciously conveying the message that they are taking a huge gamble that might result in disaster. After all, since the crash, major financial institutions around the world have been carefully deleveraging in order to meet new capital requirements.

It's also, frankly, a bit foolish-sounding. Give me a place to stand and I will move the world, said Archimedes. He didn't say he would leverage the "deliverables matrix".

Matrix

The matrix is everywhere you look in the modern office. You can have an accountability matrix (AKA a responsibility assignment matrix), a functional matrix, a project matrix and so on ad nauseam. Of course, there is even a sub-species of management called – you guessed it – matrix management.

Are all these matrices separate universes of virtual reality in which workers are drugged and asleep in a post-apocalyptic world, with a virtual reconstruction of human civilisation beamed directly into their brains so the evil masters of each matrix can use their bodies as batteries? The truth is not so interesting. What is the matrix? Basically, it's a spreadsheet.No-brainer

The phrase "a no-brainer" originated in sport, to describe a physical action in football or tennis that was so well-drilled it required no conscious thought. Its subsequent office adoption to mean "obviously a good idea", however, is both inverted boast and threat. "This is a no-brainer!" means not only "I did not engage my brain for a second in coming up with this idea", but also "You should not engage your brain in any attempt to argue with it". It is thus an announcement and a recommendation for perfect zombie-like stupidity. Photograph: Rex Features/Guardian montage

Photograph: Rex Features/Guardian montage Offline, take this

"Hey, can we take this offline?" This is a truly bizarre modern way to say: "Let's talk about it later or in private." Oh, I'm sorry! I thought we were human beings in the same room communicating with each other by making noises with our faces! I didn't realise we were online. Are we all living in the matrix now? And if we just go down the corridor to the coffee machine and talk in pairs, we'll suddenly be offline? The machines didn't really think this through, did they, if that's all you have to do to escape from your prison of virtual reality? It's a wonder they managed to take over the world in the first place.Paradigm shift

The term paradigm shift was made famous by Thomas Kuhn's 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. There, a paradigm is a whole way of understanding the world, and a paradigm shift is a dramatic transfiguration in that understanding. Paradigm shifts are hugely important intellectual developments such as "the Copernican, Newtonian, chemical and Einsteinian revolutions". Sadly, owing to the widespread phenomenon of linguistic deflation, it has since become possible to call a much less world-shattering change a paradigm shift. One educational article in Forbes ambitiously begins by sketching historic paradigm shifts – the Copernican revolution, Mendelian genetics and the guy who discovered that peptic ulcers are caused by bacteria – and then gets down to business. Now, the author claims, "a discontinuous paradigm shift in management is happening. It's a shift from a firm-centric view of the world in which the firm's purpose is to make money for its shareholders, to a customer-centric view of the world in which the purpose of the firm is to add value for customers." It probably would be a paradigm shift (to an economic epic fail) if firms really were going to abandon all hope of making money, but that is not quite the claim here. Instead, firms are going to pretend that they are not completely self-interested and really care about their customers. In the service, of course, of making more money.Quality

The ubiquitous business use of quality has become a kind of totem. Now it has been cut loose from having to be the quality of anything in particular, we can all sit around happily chanting that quality is our aim – or, in other words, that we want stuff to be … er, good? The hopeful invocation of quality is magical speech that hopes to conjure into being something that is indefinable but definitely better than flat-out rubbishness.But the insertion of quality into a business slogan or mission statement is also sometimes camouflage for less sunny intentions. In 2011, the BBC grandly announced that its plan over the next six years would be called "Delivering Quality First". (Rather than delivering TV and radio programmes first? Or perhaps they meant delivering quality first and garbage later?) But this slogan was merely a cravenly euphemistic sticking-plaster for a programme of mass redundancies. Delivering Quality First actually meant sacking 2,000 workers.

Revert

"Let me revert …" is a common way now of promising to do something. Reply? Respond? Whatever was wrong with those? (To be fair, revert could mean "to return to a person" in medieval times, so it's not a wholly novel usage.)While revert is less infuriatingly circuitous than "circle back", there is still something sonically rather unlovely about it. (Perhaps it is the echo of "pervert".) I do recommend that if anyone ever promises to revert back to you, you should shout as loudly as you can that this means "get back back", and then start doing a bad chimp dance with optional hooting noises.

Sunset

This is an imagistic verbing – "We're going to sunset that project/service/version" – that sounds more humane and poetic than "cancel" or "kill" or "stop supporting". When faced with the choice between calling a spade a spade or using a cloying euphemism, you know which the bosses will choose. Happily, sunsetting also sounds less smelly than the venerable old mothballing.Thought shower

The term "brainstorm" is now discouraged, since some people think it's insensitive to people with epilepsy, on the dubious basis that an epileptic attack is like a storm in the brain. In fact, the National Society for Epilepsy surveyed its members in 2005 as to whether they found the term "brainstorming" offensive, and a large majority said no. Nevertheless, it is more common these days to be invited to a thought shower, which no doubt sounds like a naked romp among Bergman-loving Scandinavian intellectuals only to those with already irredeemably dirty minds.The more serious problem with thought-showering is that it is rarely effective. According to the author and psychologist Keith Sawyer's account of brainstorming, "in most cases this popular technique is a waste of time". Unless thought showers are carefully planned and directed, they tend to encourage group conformity and repress individual creativity. That rather puts the dampeners on things, doesn't it?

Upskill

Have you been upskilled lately? It's an odd idea. To say that you will upskill a person seems to figure the subject as a kind of upgradeable cyborg assistant, into which new programs may, at any time, be uploaded so as to improve its contribution to profit. We are thus invited to imagine a glorious ascent of a virtual ladder of "competencies", the better to forget that upskilling usually means demanding more work for the same pay.

Vertical

Oh, right, the verticals. Yep, we need to "leverage" the "learnings" across all the verticals. I'm totally on board with that. Oh, we need to talk about "content strategy in a difficult vertical"? Sure, good idea! [Sotto voce] What the hell are verticals again?According to Forbes, a vertical is: "A specific area of expertise. If you make project-management software for the manufacturing industry (as opposed to the retail industry), you might say: 'We serve the manufacturing vertical.' In so saying, you would make everyone around you flee the conversation."

In business, there is a distinction between horizontal and vertical organisation. Apple, for example, is sometimes thought of as a vertical company because it makes "the whole widget" – both hardware and software. Vertical integration can also be a matter of owning the factories that supply your components, and so forth. In consulting lingo, meanwhile, a vertical can just be a new industry that you want to move into, by setting up a separate business unit.

The upshot of all this is that vertical in ordinary office use can almost always be replaced with "market", which has the advantage of being a word that everyone understands, and the concomitant disadvantage (for the machiavellian jargon-wielder) that it won't serve to browbeat and intimidate workers.

Oh, you know what else is vertical right now? My middle finger.

Workshop

"We're going to have to workshop that issue." Really? Office types who use workshop as a verb probably imagine doing tough things with hammers and saws and vices in a sawdust-strewn shed, so picturing the frustrating immateriality of most modern work as something nostalgically physical and mechanical. But to workshop as a verb is actually a theatrical usage that dates from the 1970s; according to the OED, it means: "To present a workshop performance of (a dramatic work), esp. in order to explore aspects of the production before it is staged formally." So next time a boss suggests something needs workshopping, gird your loins for the solemn enactment of a brutal revenge tragedy.X, theory

In the 1960s, the psychologist Douglas McGregor published The Human Side of Enterprise, which outlined two approaches to management. The first approach assumes that people hate working and crave security, and have to be forced with threats of punishment to do what you want. The second approach assumes that people like to make an effort, are better motivated by rewards and are naturally creative.McGregor called these two approaches Theory X and Theory Y. To my ears, that X makes the nasty Theory X sound rather mysterious and magical, the arena of arcane experts in the fields of physics or vast alien conspiracies (x-rays, X-Files), and so it fits perfectly with the general self-glamorising tone of modern office jargon. But it is also, of course, a boon to compilers of lexicons who otherwise wouldn't have anything to put under X, so you won't hear me complaining any further about it.

Yield

Don't ever say that your plan will "give" or "cause" or "result in" great things; the only verb to use here is yield.The word probably appeals to management types for two reasons. The first and more obvious is that yield is also a noun in finance meaning the expected income from a bond or other holding. The second reason, I suspect, is an obscurely martial or psychosexual one: because to yield also means to give way or to admit defeat, the thrusting manager who sees everything yielding before him is subconsciously picturing the ground strewn with defeated enemies or willingly passive sex-partners.

Zero cycles

Zero cycles is how many bicycles you have when you don't have any bicycles. Perhaps you are a sad clown whose entire clown act is about lamenting the lack of bicycles in your clown life. Alternatively, you can speak as though you were a computer that has a finite number of "cycles" of its internal clock to perform calculations within a given time. So you can say, in response to a request that you do some extra work: "Sorry, I have zero cycles for this." It's a splendidly polite and groovily technical way of saying: "Bugger off and don't ask me again."

Extracted from Who Touched Base In My Thought Shower?: A Treasury of Unbearable Office Jargon by Steven Poole, to be published by Sceptre at £9.99 on 31 October 2013. Order a copy for £7.99 with free UK p&p from guardianbookshop.co.uk