Move over, George Orwell – this is how to sound really clever

A

new book lists 600 words to use if you want to impress. But when is it

appropriate to deviate from plain English and indulge in sesquipedalian

behaviour?

[From The Guardian]

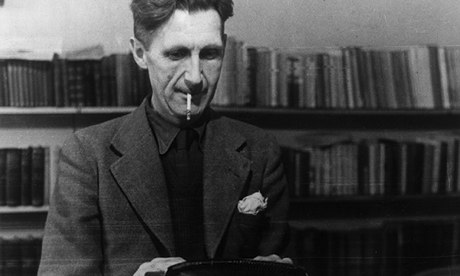

George Orwell: never use a sesquipedalian word where a short one will do. Photograph: Mondadori via Getty Images

Aged 17, I heard a confession that I found exhilarating. Mr

Downs, my English teacher, confessed that he'd read the dictionary.

Cover to cover. Most sixth-formers at my Ofsted-scourging school scoffed

at this peculiarity. I fell hopelessly in love with him.

A man with a big diction will often impress. But he doesn't impress everyone. Some – such as George Orwell - argue that it's not the length of the words that count, but how you use them. "Never use a long word where a short one will do" and "never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent", he advised in his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language – the journalist's unofficial bible.

What, then, are the merits of elaborate language and when is it appropriate to use it? How To Sound Really Clever (Bloomsbury) lists 600 words that give you a "delightful rush" when you discover what they really mean, where they come from, and how to use them correctly. It's a sequel to How To Sound Clever and features the "slightly more distinguished, complex cousins" to the words in the first volume.

When I interview the author, Hubert Van den Bergh, he's quick to point out that some journalists have discarded their bible; many of the words he selected were taken from newspaper articles. The most common inspiration was the Daily Telegraph. Many words in the book were completely new to me and discovering them was like tasting ice-cream for the very first time.

There are certainly times I've felt acedia (unaccountable melancholia) without knowing what to properly call it. If you feel it constantly, it may be that you're anhedonic – unable to feel pleasure. After studying this book, you could say that words are your bailiwick – area of authority or skill. Use them too manipulatively, though, and you may be accused of being casuistic – clever, but intellectually dishonest.

A cognitive dissonance means having inconsistent beliefs, usually about one's own behaviour. Gay Catholics fall into this category. The opposite of nocturnal? It's diurnal. Certain lyrics of Madonna? They're doggerel (appalling poetry). An epigone of Madonna? Lady Gaga (it means an inferior imitator).

I've worked for eight years in the voluntary sector and not once did I realise that my profession could be called eleemosynary (relating to charity). The immediately evocative hagridden means to be harassed by a negative emotion.

I discovered an alliterative synonym for one of my favourite unusual words, saturnine – subfusc, meaning gloomy. Verisimilitude (the appearance of reality) takes me back to my university days, when I used it in as many essays as possible. I probably thought I sounded clever. This is the first time I've used it since.

Word number 598 in the book is my favourite for concisely encapsulating a complex figure of speech in just a few letters. Zeugma is when a word applies to two others in different ways; or to two words when it only semantically suits one. An example of the former quotes Alanis Morissette: "You held your breath and the door for me." How chivalrous and zeugmatic. An example of the latter is "with wailing mouths and hearts" – but don't blame Morissette for this doggerel.

This book is about more than clever words. Fascinating etymologies are also revealed. So a canard, a false rumour, comes from the French for "duck" because of a remarkable habit they have. When a predator approaches its young, the parent will feign a broken wing, depicting themselves as the easier target. This distraction gives the ducklings the opportunity to escape, and the deceptive duck will then take off at the last minute.

Meanwhile, pudenda (a woman's external organs) comes from the Latin pudenda (membra) – (parts) to be ashamed of, from pudere (to be ashamed). This traces back to a long and unfavourable etymological history relating to women and their bodies.

Something that does stand out is how many apt or ironic words the book contains. So although it is compendious (succinctly containing all the essential facts), it may encourage a cursory (hasty and not thought through) use of the words it explains. It could result in fustian (pompous) communication or lucubrations (pretentious, laboured writing). Nevertheless, you could rarely be accused of using pabulum (trite words). But avoid plain English altogether and you could end up being periphrastic (speaking in a roundabout way). Get too carried away and you'll certainly become pleonastic (using superfluous words). And use words like sesquipedalian and you'll already be displaying sesquipedalian behaviour (it means using long words).

As for Orwellian plain English, Van den Bergh claims that many find him "just too Spartan" and can't finish his books. Although he grants that Orwell conveys his meaning very precisely, he highlights a flaw in his utilitarian style: "He allows no flights of fancy. Interaction is more than just the conveying of a meaning – a bit of entertainment and relish is usually welcome, too."

Of course, there can be consequences of using elaborate language when a plain English alternative will suffice. It leads to such appalling euphemisms as "collateral damage". Charles Dickens highlighted these consequences most poignantly when he called Oliver Twist an "item of mortality" in the first line of the novel. Words, used well, should aid meaning, not conceal it, distract from it or dehumanise it.

"Usually people enjoy the colour an unusual word provides," Van den Burgh says. I can't help but agree. At 17, life went from monochrome to multicoloured – even if it sometimes led me to fustian, sesquipedalian and pleonastic lucubations.

A man with a big diction will often impress. But he doesn't impress everyone. Some – such as George Orwell - argue that it's not the length of the words that count, but how you use them. "Never use a long word where a short one will do" and "never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent", he advised in his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language – the journalist's unofficial bible.

What, then, are the merits of elaborate language and when is it appropriate to use it? How To Sound Really Clever (Bloomsbury) lists 600 words that give you a "delightful rush" when you discover what they really mean, where they come from, and how to use them correctly. It's a sequel to How To Sound Clever and features the "slightly more distinguished, complex cousins" to the words in the first volume.

When I interview the author, Hubert Van den Bergh, he's quick to point out that some journalists have discarded their bible; many of the words he selected were taken from newspaper articles. The most common inspiration was the Daily Telegraph. Many words in the book were completely new to me and discovering them was like tasting ice-cream for the very first time.

There are certainly times I've felt acedia (unaccountable melancholia) without knowing what to properly call it. If you feel it constantly, it may be that you're anhedonic – unable to feel pleasure. After studying this book, you could say that words are your bailiwick – area of authority or skill. Use them too manipulatively, though, and you may be accused of being casuistic – clever, but intellectually dishonest.

A cognitive dissonance means having inconsistent beliefs, usually about one's own behaviour. Gay Catholics fall into this category. The opposite of nocturnal? It's diurnal. Certain lyrics of Madonna? They're doggerel (appalling poetry). An epigone of Madonna? Lady Gaga (it means an inferior imitator).

I've worked for eight years in the voluntary sector and not once did I realise that my profession could be called eleemosynary (relating to charity). The immediately evocative hagridden means to be harassed by a negative emotion.

I discovered an alliterative synonym for one of my favourite unusual words, saturnine – subfusc, meaning gloomy. Verisimilitude (the appearance of reality) takes me back to my university days, when I used it in as many essays as possible. I probably thought I sounded clever. This is the first time I've used it since.

Word number 598 in the book is my favourite for concisely encapsulating a complex figure of speech in just a few letters. Zeugma is when a word applies to two others in different ways; or to two words when it only semantically suits one. An example of the former quotes Alanis Morissette: "You held your breath and the door for me." How chivalrous and zeugmatic. An example of the latter is "with wailing mouths and hearts" – but don't blame Morissette for this doggerel.

This book is about more than clever words. Fascinating etymologies are also revealed. So a canard, a false rumour, comes from the French for "duck" because of a remarkable habit they have. When a predator approaches its young, the parent will feign a broken wing, depicting themselves as the easier target. This distraction gives the ducklings the opportunity to escape, and the deceptive duck will then take off at the last minute.

Meanwhile, pudenda (a woman's external organs) comes from the Latin pudenda (membra) – (parts) to be ashamed of, from pudere (to be ashamed). This traces back to a long and unfavourable etymological history relating to women and their bodies.

The

term salad days (time of youthful inexperience and indiscretion) is

from one of Britain's most prolific neologists – William Shakespeare –

who in Antony and Cleopatra compares youthfulness to a salad "green in

judgment, cold in blood".

Commonly misused words are clarified.

Enormity doesn't mean vast size (that's enormousness) – it means a grave

crime. Disinterested is about money before it's about boredom (having

no financial interest in one particular outcome or another). Nonplussed

is the most interesting: it has come to mean two antithetical things.

The original definition is that you're so surprised you're unsure how to

react. More recently, it has started to be used for feeling unperturbed

– the exact opposite of shocked. The author notes that "both meanings

are fighting it out" and recommends avoiding it altogether until this

semantic battle is won.Something that does stand out is how many apt or ironic words the book contains. So although it is compendious (succinctly containing all the essential facts), it may encourage a cursory (hasty and not thought through) use of the words it explains. It could result in fustian (pompous) communication or lucubrations (pretentious, laboured writing). Nevertheless, you could rarely be accused of using pabulum (trite words). But avoid plain English altogether and you could end up being periphrastic (speaking in a roundabout way). Get too carried away and you'll certainly become pleonastic (using superfluous words). And use words like sesquipedalian and you'll already be displaying sesquipedalian behaviour (it means using long words).

As for Orwellian plain English, Van den Bergh claims that many find him "just too Spartan" and can't finish his books. Although he grants that Orwell conveys his meaning very precisely, he highlights a flaw in his utilitarian style: "He allows no flights of fancy. Interaction is more than just the conveying of a meaning – a bit of entertainment and relish is usually welcome, too."

Of course, there can be consequences of using elaborate language when a plain English alternative will suffice. It leads to such appalling euphemisms as "collateral damage". Charles Dickens highlighted these consequences most poignantly when he called Oliver Twist an "item of mortality" in the first line of the novel. Words, used well, should aid meaning, not conceal it, distract from it or dehumanise it.

"Usually people enjoy the colour an unusual word provides," Van den Burgh says. I can't help but agree. At 17, life went from monochrome to multicoloured – even if it sometimes led me to fustian, sesquipedalian and pleonastic lucubations.